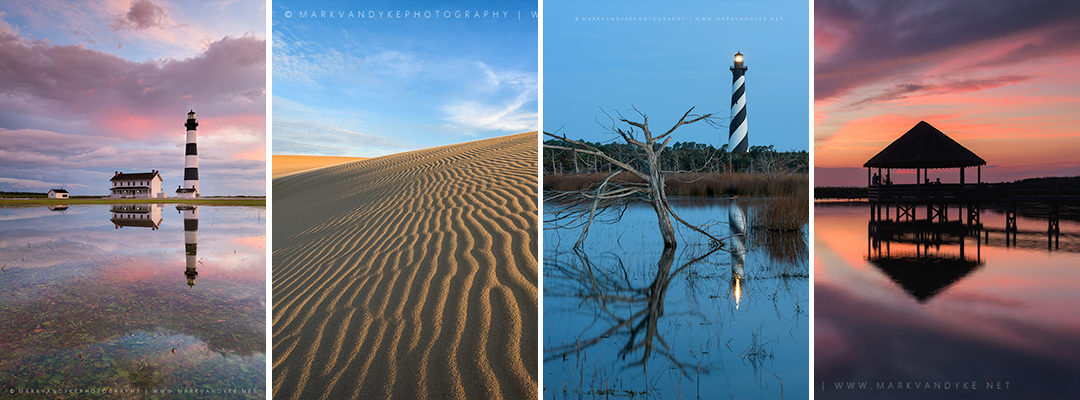

Photo Essay: My Outer Banks

Photography is a game of vision, and vision is unique to each photographer. How each of us views a place is some complex derivation of personal experiences, learned knowledge, and personal attributes—all of which cannot be duplicated, only imitated. It’s my belief that if we want to render unique and powerful photographs of place we must first understand ourselves and second develop a relationship with the place (and it doesn’t have to always be a friendly relationship either—knowing why you dislike/fear/are uncomfortable is just as important). The more intently we honor who we are uniquely within a place—what we notice/don’t notice, how we feel/don’t feel–and translate that emotion and understanding into our photographs through subject choice, composition, colors, mood, technical decisions etc., the more others will engage us and our work meaningfully. This blog is about my own experiences, my own memories, my own understandings of the Outer Banks of North Carolina: this is my Outer Banks.

I’ve been visiting the Outer Banks my entire life, long before I can even pull meaningful memories. My folks often reference momentous events that we all experienced there as family, my sister, mother and father and I— things I should remember, like riding out a hurricane in a rental home. Details like mattresses off the bed and over top of us in the hallway or was it the bathroom (wait, weren’t we on stilts?). I don’t remember any of that. The truck my father used to drive out onto the isolated deep sand beaches to fish the surf. A smaller world where the only technology available to understand an ominous advancing sky was the radio. I don’t remember any of that either. Too young I guess. I do know that the choice my folks made to visit the Outer Banks shaped and spoiled my own vision of what a proper beach should be and very few if any locations have ever measured up to the Outer Banks.

To understand my fondness for the Outer Banks, I have to first introduce you to my roots. I grew up in Northern Virginia, a region that could be characterized as a giant succession of interconnected subdivisions for the workforce of Washington D.C. It was a landscape of rapid change—rural land was being transformed in the blink of an eye to become something more: a wider road, a shopping center, a town center, a new school. Growth was evident everywhere and it was the theme of my early years. There were few to no natural anchors in the landscape, the only exception being the Potomac River, which, despite its relatively large size, seemed inconsequential in the region when compared to the development occurring all around it. What was familiar one year was something entirely different the next. And there were no boundaries to the growth (few remain still to this day as West Virginia has become the new frontier for those willing to drive long distances to work). Public versus private became a critical distinction with regards to green space. Shrinking pubic natural resources meant increased rules on what remained: rules about when and how an area could be used, if at all. For me, as a boy, while the physical area of Northern Virginia might have remained the same, things were getting much smaller. Economic and social opportunities were being substituted directly for environmental opportunities whether I cared for them or not. This thread of inquiry/curiosity/conflict–the trade-offs accompanying increased development and its effects on public green space–drove me later to nearly a decade of studies within higher education regarding sustainability and the built environment.

Enter the Outer Banks of North Carolina, a place apart; different; special to me. The Outer Banks, you see, are a place dominated not by economic or social development but by the very environment itself. Nature is king in the Outer Banks and if you forget, it will surely remind you. Bounded on either side by massive bodies of water—the Atlantic Ocean to the east and the Pamlico Sound to the west—the thin strip of sand known as the Outer Banks somehow balances magically between a vast landscape of blue sky and blue water. With the exception of an artificial line of primary dunes, one could look in either direction over largely flat topography and see endless water. Unlike Northern Virginia, where economics ran over everything with silly ease and the natural environment was relegated to tiny dog parks and artificial ponds–afterthoughts to be heavily managed with rules and regulations–the Outer Banks (at least the sections that my family and I visited) were deemed National Seashore and protected at the highest levels. Here in the Outer Banks I had found a vast outdoor playground of rich resources: deep sands, large surf, open beaches (at that time), few to no rules or regulations or enforcement for that matter (no longer the case) and natural beauty everywhere. And the people…these were not the types of folks who played dress up each day and ignored the weather, moving from home to automobile to office to home. No, the folks who thrived on the Outer Banks—commercial fisherman and outdoor recreational enthusiasts (surfers and the like) had a seemingly intimate relationship with the wind and the waves; a respect that showed a mutual understanding for the impact that these forces could have on their quality of life at any given moment. This was a place very apart from that which I knew; it was a place that deserved greater attention, and for me at least, a place that deserved my admiration and respect. It’s through that lens that I’ve come to know and experience the Outer Banks. Though changed today, I will always view the Outer Banks as a place of great freedom, of outdoor pursuits, and a place that calls to those who wish to live in the heavy presence of the natural world.

The Outer Banks are roughly five hours by car from Northern Virginia. However, my Outer Banks experience typically begins well before arriving, at a series of local produce stands along Caratoke Highway (US-168). You might recall, if you’ve ever taken this northern approach to the Outer Banks, the endless parade of signs for Powell’s Roadside Markets. Sign after sign standing in front of agricultural fields advertising fresh fruits and produce: watermelons, berries, tomatoes, peaches. These stands were doing the local thing long before farmer’s markets became the latest and greatest fad. They stood in stark relief to the fancy grocery stores of my youth back in Northern Virginia. Often, the produce stands themselves were part of a larger farm and fields, the grounds littered with tractors and other farm implements. Everything about these roadside businesses screamed local, fresh, and authentic long before those words were all the rage. My family and I would often opt to skip right on by the Powell’s Roadside Markets (which were very good as well) in favor of Morris’ Roadside Market, a rather large operation (and growing still) that has all of the colorful goods mentioned above, as well as sweet treats like ice cream and just about every conceivable flavor of cider you can imagine: traditional apple cider, tart blackberry cider, sweet strawberry cider. I can recall the way my father would get excited about picking the perfect watermelon or cantaloupe or tomatoes and how I would wonder why these particular melons were better than the ones that he got back home. I think I’m beginning to understand now.

About an hour after the produce markets began to disappear in the rearview mirror, the towns of Kitty Hawk and Nags Head took center stage–the central towns of the Outer Banks–as well as the turn off for the northern Banks (Duck and Corolla). While I’ve developed a better appreciation for these areas today, most of my younger years I think we all as a family tried to pass through or avoid these areas as quickly and thoroughly as humanly possible. See, Kitty Hawk, Nags Head and the northern Banks represented the last vestiges of what we were trying to escape: retail malls, chain stores, hotels, fine dining, sameness. They lacked “wildness”. We rarely stopped. I think we all sort of held our breath as the car rolled south at fifty miles an hour through a dizzying array of stoplights and the assault of haphazard development until we saw the large brown signs for Cape Hatteras National Seashore at Whalebone Junction (at least I did). A sharp left turn onto NC-12, now known as the Outer Banks Scenic Coastal Byway (or something like that—locals always just called it the beach highway), and the world began to change into the Outer Banks that I knew and that I envision to this day. The road and the island slowly narrowed in width, the last of the beachfront homes in southern Nags Head fading away to the east. First a sign for the Bodie Island Lighthouse, then the Oregon Inlet Campground and Marina, and then, finally, the Bonner Bridge.

The Bonner Bridge, an elevated concrete causeway with a hump in the middle to allow marine traffic to pass through Oregon Inlet below, was my mother’s biggest fear. What if there were an accident and the electric windows didn’t work? You see, she didn’t know how to swim and this elevated causeway places the traveler miles out from the mainland high above a vast amount of water. I always believed that her fear was irrational, but then again I could swim quite well and I didn’t worry about the electric windows! It was only later that I learned what poor structural condition the bridge actually was in, the thought of which combined with my mother’s fear still makes me smile as I cross today. Unlike the Ravenel Bridge in Charleston, South Carolina, a structure functioning as a statement piece of architecture, lit up at night like an expensive piece of jewelry, the Bonner Bridge in the Outer Banks of North Carolina is a humble and efficient structure fitting the spirit of the place. Cresting the top of that hump on the Bonner Bridge—an elevated perch high above the surrounding sand spits allowing views as far as the eye can manage of shimmering blue water—only then was I ‘there.’ It was at the top of the Bonner Bridge heading south where my Outer Banks began and still begins today. Everything before the bridge was just normal, ho-hum, everyday. Everything after was different, somehow more exciting and adventurous. The Bonner Bridge set the stage for my own experiences in the Outer Banks.

On the southern side of the Bonner Bridge is Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, a vast area of undeveloped beach and sound front rich with marine life, birds, and unspoiled landscapes. When I was younger it all seemed much more natural: there weren’t pieces of yellow construction equipment lining the roadway constantly rebuilding artificial dune hills to prevent breach and highway flooding. I’m not sure that anyone, aside from some natural scientists perhaps, understood that the migrating Oregon Inlet and consequent dredging would rob so much sand from the dunes at Pea Island. This has become an area of much political and environmental conflict for the Outer Banks—an age old struggle between the costs of building what’s needed to provide the services that society desires versus the environmental reality of the place. However, when I was just a boy, passing through Pea Island was very different; it served to reset my mindset. I began to relax, to pay more attention. It all seemed like an adventure, the car so smoothly gliding over a strip of black asphalt only feet from the Atlantic Ocean on one side and the Pamlico Sound on the other. My mother always said that the island was moving, but I couldn’t understand what that meant. I never felt the island moving—I couldn’t see it. And I certainly couldn’t fathom, driving down that highway, how the activities back at Oregon Inlet could impact the sand and road miles away on Pea Island. It took years for all of that to make sense.

Heading south along NC-12 a series of small villages materialize: Rodanthe, Waves, Salvo, Avon, Buxton, Hatteras. These towns were local in every way. The built landscape was neither garish nor attention grabbing. Homes were entirely wood, from the deep pilings to the wrap around decks. Everything was a humble weathered brown. I developed an intense interest in carpentry from my early visits to the Outer Banks. I watched with great interest as new vacation homes were constructed. The materials would take on such a dignified and aged look shortly after construction (today new building materials like fiber cement siding have introduced some of the colorful kitsch that has robbed the widespread humility that I once found so fitting for the Outer Banks). Chain development was banned by law: no McDonalds or Taco Bells or other marketing bombs invaded the precious spit of land. For the longest time there were none of those large block Waves stores where the business was perpetually having a “going out of business” sale year after year after year: everything 50% off! Instead, there were local arts and crafts stores, restaurants, seafood shacks, ice cream establishments. The villages of the Outer Banks were incredibly local, humble places inhabited by resilient people who seemingly put the place above all else. It was enough just to be there. It was different and it was special, not only to me it seemed, but to everyone who chose to make their lives there.

My family would typically stay in the town of Avon, or later in the town of Frisco, my mother pining for an oceanfront or soundfront rental where she could enjoy the water views from the balcony or backyard. My father and I would slip away in the dark hours of the morning to jig for trout in the sound. My sister would seek the company of other young folks, meeting up at beach bonfires or at the local fishing pier. Afternoons were spent rounding up willing (and sometimes unwilling) family and bystanders for games of sand volleyball. I loved to swim in the ocean, or more accurately, I had a strange fascination with getting worked over by active surf, letting myself get tossed around and crashed into the sandy ground just to experience and appreciate the power of the waves, my eyes burning red from hours of saltwater and sunlight exposure. There were hours and hours of fishing, first from the surf and then more actively wading around in the sound, learning patience and the practice of sinking into my own thoughts as I literally melted into the landscape around me, my reflexes sharp for the tickle of something on the other end of my weighted presentation while my mind wondered near and far. And there were the unforgettable apple ugly donuts that would appear on the table from time to time as if by magic, the sight of a greasy white paper bag all I needed to trigger excited recognition that my father, having slipped out to the store during the morning, must have stopped at Orange Blossom Café in Buxton on the way back.

Somewhere down the road came the camera—a new passion. The trips have changed. I travel alone much of the time now, although my family still tries to visit at least once a year (even my sister, who now resides in Alaska attempts to make the trip as often as she can). My accommodations are at the campground where the heat and mosquitos and the sun are felt more acutely than I remember. I don’t drive a truck anymore as the fuel costs and beach access permits exceed my earnings as a full-time photographer. My alarm still signifies a sunrise adventure; however, my tools are no longer a set of waders and a fishing rod but a tripod and a camera. All of my experiences, remembered and perhaps even not so well remembered, shape and mold my vision of the Outer Banks, wrapping and intertwining themselves like rope into all of my photographs. It’s all there. I feel it when I’m taking the photos. I recognize it when I’m viewing the photos. No one will experience the Outer Banks the same way as I did and no one should interpret it the same behind the lens now. That’s the amazing thing about landscape photography—as a means of communication the craft allows each of us to share a bit of ourselves through the places that we cherish. And the motivation to be a better photographer has nothing to do with sharper pixels edge-to-edge or more accurate color rendition or finding more dramatic skies. At least it doesn’t for me. As the photographer, no matter the subject or the place, I’m in every photograph that I take. It’s the desire to make that connection—the connection between myself and the viewer–clearer and stronger that drives improvement efforts; to know that someone else “gets it.” That someone else could imagine how it felt to be at the Outer Banks; to feel the ocean around my ankles as I photographed a sunrise; or to witness the weight of night as it closed in around a long summer day with its intense blue hues; or to comprehend the significance of a lighthouse within the broader maritime landscape; or to simply ignite imagination towards a sentiment of wonderment and awe for a place so full of natural beauty.

I would love to hear about your experiences along this strip of barrier islands on the North Carolina coast! Tell me in the comments below what you think about when you envision the Outer Banks. What does this place mean to you?