Disoriented. That’s the feeling I had when I arrived on the Cape this past September for the first time. I had the opportunity to travel north to Cape Cod National Seashore with my sister (visiting from Alaska) who was attending a conference in Brewster, Mass. Admittedly, I did little to no prep work beforehand to research the area and the opportunities I would encounter. Outside of a few broad image searches on the popular online engines, I wanted my visit to be completely from-the-hip, unplanned, instinctive, go-with-the-breeze. Cape Cod National Seashore is well outside of my normal operating range in the Carolinas and thus, I wanted to treat the trip as an experiment of sorts and man, was I lost and without direction!

My predominant experience within National Seashore is from extensive visits to Cape Hatteras National Seashore in North Carolina. There’s no mistaking the geography in Hatteras; no question as to where the sea and the sound are. Turn your head one direction and you’ve got the ocean: the other and you’ve located the sound. Landmass is flat, at or below sea level, rising only at the line of primary ocean dunes. Move your feet too far in either direction and you’re bound to get wet. I brought those generalized expectations with me up to Cape Cod National Seashore, assuming that attaining a directional feel would be as easy as finding the sea and going through the normal exercise of orienting off said point. Who would’ve thought that finding the sea would be difficult?!

We bookended our trip on the Cape camping at Nickerson State Park, a very large property in Brewster, Massachusetts that is heavily wooded and features a number of kettle ponds—beautiful freshwater bodies that are the results of historic glaciation. Nowhere were the expansive sand dunes, ocean and salt marshes that I expected to see. Instead, there was an abundance of tall trees, vegetation, and fresh water. I was completely disoriented as my expectations met the reality of the place. I spent the entirety of the next day driving up and down the coast getting my bearings and doing what photographers most often describe as “scouting.” It’s easy to think that as a photographer you’re just going to blow into town and light up the memory card with your uncanny skill behind the camera, but, it doesn’t work that way. It’s knowledge of a place borne over time and experience that wins every time: knowing where the sun rises and where it sets; where fog most likely occurs when conditions present; where shots can be most productive on clear, blue sky days; where to go when it’s too crowded at the well-known places; where seasonal elements like blooms/blossoms/color change etc. happens. It takes years to develop that sort of rapport with a place. With that said, I was just hoping to get myself into the right place at the right time at least once or twice while also enjoying my time as a tourist in this new place.

Thick fog obscured the horizon at Flax Pond within Nickerson State Park in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. This beautiful freshwater body was the result of historic glaciation. Our campsite afforded us easy access for photography and the occasional afternoon swim!

Similar to NC-12 (the Outer Banks Scenic Byway) in North Carolina, Cape Cod National Seashore has one primary road for visitors to explore: Route 6 and 6A. I always felt a sense of peace and relaxation when I hit NC-12 in my automobile. Rising high above the watery landscape over the Herbert Bonner Bridge and then passing through the desolate Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge hugging the primary dunes and viewing the ocean and sound on either side of the asphalt ribbon was like a cleansing. Route 6 in Massachusetts was not the same experience. Coming into Brewster, Massachusetts, Route 6 (also formerly known as suicide alley for the frequency of head-on collisions) is a two lane freeway with a heavy median of constant colorful plastic stanchions. I didn’t understand the setup until I went online to research the need for such efforts to separate traffic. Further, there are tall trees on each side of Route 6: you can’t see, hear or smell the ocean. There were no obvious environmental markers to indicate how near to the coast I was as I motored into the lower Cape. Upon arrival in Brewster, it still took me some time to realize that all of the local “beaches” were not beaches in the classic sense of Atlantic Ocean and waves. They were access points to beautiful tidal flats along Cape Cod Bay and Nantucket Sound. It wasn’t until I ventured to the Outer Cape that I finally found the classic beach scene of the Atlantic Ocean lapping at sandy beaches. The size of Route 6 (lanes, ramps, traffic) also spoke to a place much larger and more connected to the mainland than my experiences with Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

The week proceeded with my personal education on Cape Cod National Seashore. Cape Cod is not flat; it is not a barrier island at the mercy of the sea like Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Most of the beaches along Cape Cod National Seashore feature beautiful, tall sand cliffs that place land and visitor well above the fray. It is a breathtaking way to have your first introduction with the coastline (from far above). I stood on the observation stair at Marconi Beach in Wellfleet and had to admire the height and size of the sand cliffs—it was unlike anything I’ve seen before on the East Coast. Homes are not built on stilts in the Cape, rains do not flood the roads with standing water, and vegetation is not severely limited in height or flagged in shape by wind-driven salt spray from the ocean. Life over the primary dune is largely unaffected by the sea itself compared to Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Further up the Outer Cape in Provincetown the primary dunes (foredunes) morphed into elaborate dune fields, massive and supremely impressive in their quantity and size. These are known as parabolic dunes and are extremely unique to this area of the east coast. Unlike the constant battle along the coast of North Carolina against the loss of sand in the foredunes of Cape Hatteras National Seashore, these parabolic dune fields in the Province Lands of Cape Cod are the result of the exact opposite: a steady stream of accreting sand from along-shore currents. The battle here is not to keep the sand from being reclaimed by the sea but to keep the sand from literally consuming geographic and man-made landscape elements! Perhaps the most “wild” and exciting area of Cape Cod for me personally was the Snail Trail over the parabolic dunes in Provincetown. I wish I had more time to explore this area and to wait out spectacular skies and conditions. It was truly an amazing landscape to traverse and photograph! I didn’t spend much time around Provincetown proper, but I did come to understand its, let’s just say, colorful culture and reputation. That artistic bent leaked over onto an abandoned structure I found within the Province Lands that featured some fresh graffiti of a Great White Shark by Poyse (shout out to the artist). My recommendations to any traveling photographer new to the Cape would be to concentrate efforts on the capture of the parabolic dunes in the Province Lands.

The parabolic dunes of the Province Lands in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Unlike the eroding sand that I’m used to in the Carolinas, these dunes were accreting and building. These areas were easily my favorite for exploration and subjects behind the camera.

Beaches along Cape Cod National Seashore do not feature quantities of shells. Instead, they have rocks and pebbles. Don’t let that fool you though. The quantity and variety of stones able to withstand the beating of the Atlantic Ocean provides opportunity to beachcomb just the same with different colors, shapes, and textures to be found. From my limited understanding, the presence of stones on the beach is the result of glaciation and the fact that Cape Cod sits atop quantities of bedrock beneath glacial sediment. Either way, it was unique and different to see quantities of well-worn stones along the seashore.

Rocks instead of shells. That was different! Beachcombing takes on a new definition when the treasures are rocks.

One of the neatest discoveries along the Cape was the presence of some late season Beach Plums. I’m a huge berry fan. Thus, the discovery of a new-to-me species of edible berries was pretty exciting. On one of our initial scouting walks in the forests high above the shoreline we ran across a number of late summer/early autumn berries. One that neither of us recognized was a large blue/purple berry that had the texture and consistency of a blueberry, only larger and with a stone pit. With a bit of research I was really excited to discover the intriguing story of beach plums (as well as mushrooms) and their colorful history along the Cape with locals who all have secret wild locales. Beach plums are used for a number of local delicacies, the most common being jellies and jams. In the spirit of the articles I read online, I’ll be nondescript with the location of the beach plums I found on the Cape 🙂 While I did taste several in the field, I didn’t have the opportunity to locate and purchase any jams/jellies/liquors that were made with the unique berry. Something for a future trip I guess!

We were extremely lucky to travel to the Cape during the first weekend of the “off-season.” If not, it appears that crowds would’ve been high, access would’ve been extremely restricted, and local beaches and parking areas likely would’ve been out of the question for us. Unlike the vast, uncrowded, free access to Cape Hatteras National Seashore (except for the new 4×4 permits), Cape Cod National Seashore’s public parking areas all cost $20.00 per trip and had strict hours, two restrictions that would’ve made photography damn near impossible in-season. Luckily for me, it appeared that the season was over and the rangers and lots were all but abandoned for the season. I would ponder a guess that most local photographers relish the off-season as they regain their freedom and access to countless beaches and access lots. I can’t imagine visiting during the busy tourist seasons. Perhaps one of the best examples would be sunset at Rock Harbor in Orleans. This is one of the only “free” lots and is apparently one of the most crowded places to take in a spectacular sunset during the summer months. Luckily, access was easy each time I tried this past September and wading around the tidal flats was one of the highlights of my trip. Rock Harbor was definitely a spectacular vantage for sunset.

The clam trees of Rock Harbor, MA. These trees were used as channel markers and provided a very unique and beautiful photography subject in the shallow tidal waters at sunset.

Overall, Cape Cod National Seashore was a beautiful and unique coastline, featuring many plants and animals that were new to me. I got to taste my first beach plum, as well as witness large groups of seals at Coast Guard Beach. While I was a bit early for the annual Cranberry harvest, I did get to travel sections of the Cape Cod Rail Trail by foot, as well as walk through the parabolic dunes of the Province Lands. My sister and I swam through the clear, cool waters of a kettle pond at Nickerson State Park: okay, she swam while I found high perches to dive awkwardly off of! It was good fun exploring a new place. What’s my overall impression? I’m still a Carolina guy and will continue to dream about time in the Outer Banks and Cape Hatteras National Seashore. However, I don’t regret the trip up to Cape Cod and I wouldn’t be surprised if I ended up back for some more exploration in the future–in the offseason of course! The best part for me…I got to develop knowledge of a new place, a new environment, a new opportunity. The more I can go through this process of learning new places and new patterns, the better I will inevitably perform behind the lens and the more aware and engaged I’ll be in my life overall!

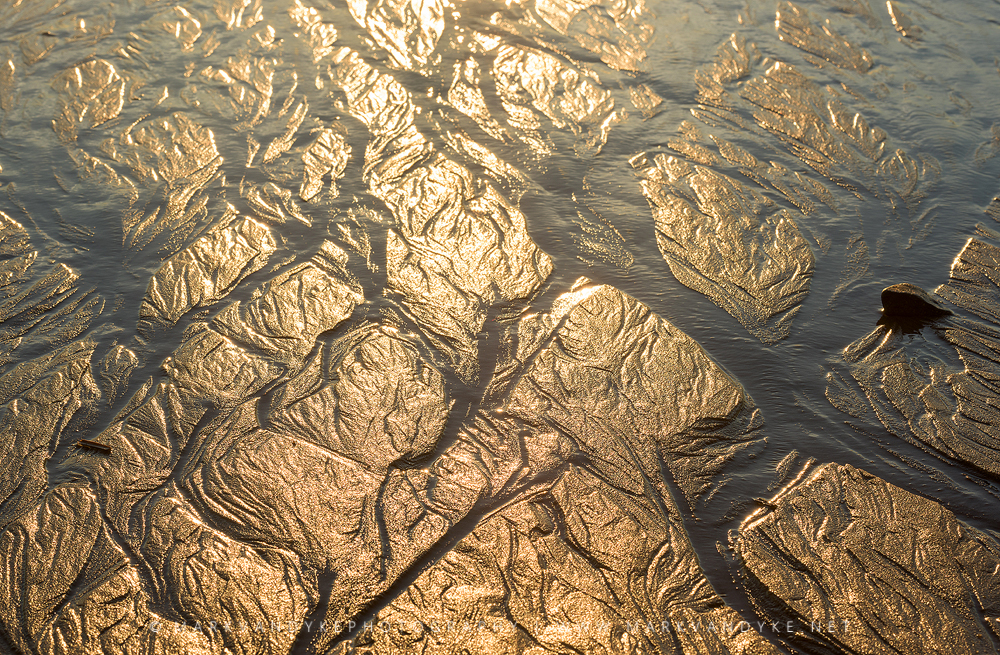

Tides along Coast Guard Beach–part of Cape Cod National Seashore–created amazing textures and shapes along the beach.

Published: National Parks Magazine Winter 2021

PUBLICATION: National Parks Magazine ARTICLE: The Earthest Edge PHOTO USE: 1/4 page spread, pages #52I was honored to place a photograph within the Winter 2021 issue of National Parks Magazine, the publication of the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA)....

0 Comments